What even is wellness?

There's a simple explanation, but you might not like it. It's why wellness is shockingly easy to brand and sell.

I am loved. I am enough. I am … well.

It’s one of those terms that seems evident, but it’s vague. Wellness isn’t anything specific. Is it a feeling of wellbeing? It can’t be, because juice cleanses and microneedle treatments are wellness. Is it things that improve your health? That doesn’t explain the dangerous treatments like jade vagina eggs and all-meat diets. Is it an all-around improvement in quality of life? All of the above contradict that. Might it be a badge to identify and attract already near-perfect people who want to be seen improving themselves?

Actually, that seems to be it.

As an example, let’s look at some main definitions of wellness. Most of them disagree with me, but more important, they all disagree with each other. This is a crucial detail. You’ll see why.

The definition with the best SEO is the Global Wellness Institute.

It leads to health. Great. In today’s climate, that means a solid base of securing enough calories, funds, sustainable housing, and time to rest. Wellness must be big on the base needs for health.

Here’s another one, the 12-part wellness wheel.

That covers everything a body can do but not everything a body needs. Now we see a transcendental element. If you know your psychology of needs, you’ve noticed that the person this benefits already has enough, but they want more.

Well, let’s try Wikipedia, both the most accessible and underrated source for this stuff.

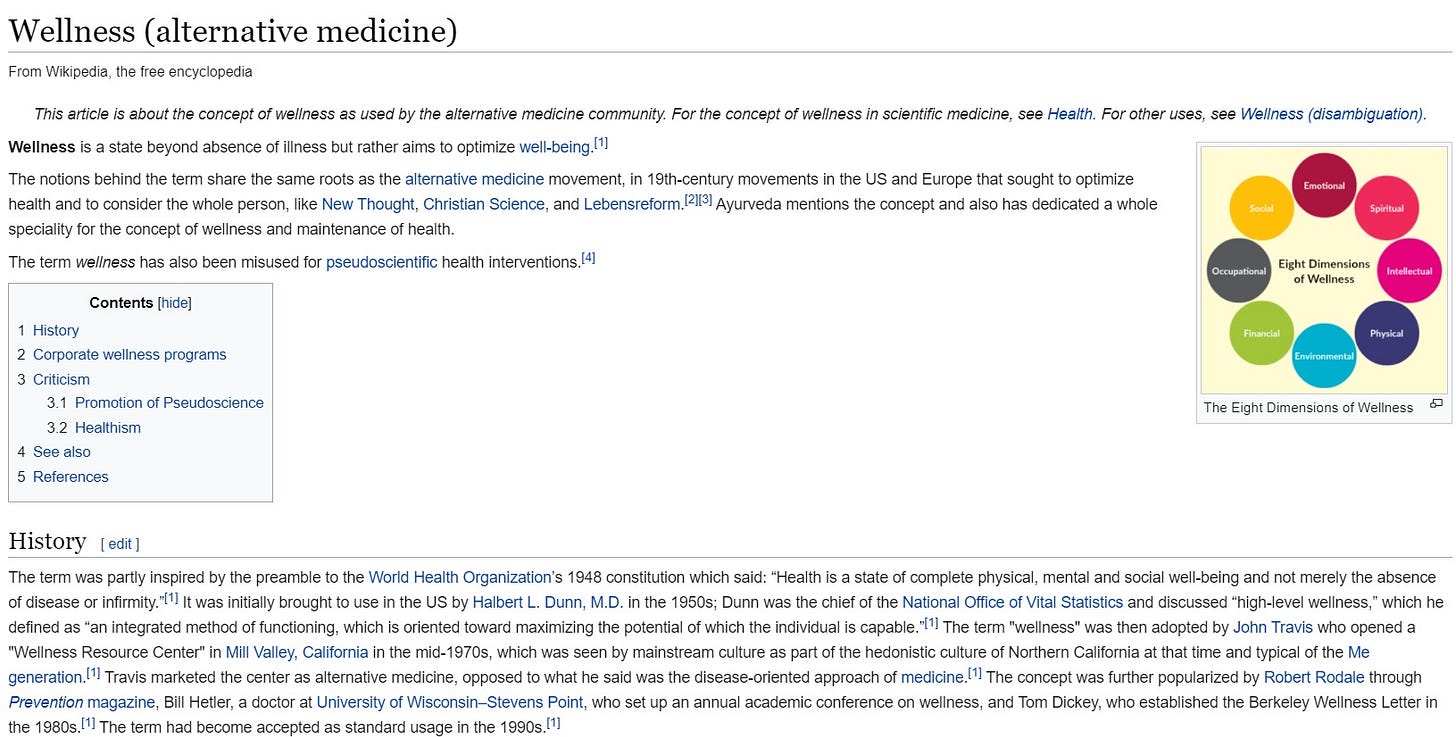

There it is. The first sentence doesn’t read like a self-contained article, but as a response to something. “Actually it’s a state beyond absence of illness. We want to optimise.” And their wheel only has eight vaguer parts. Notice how no one has given a single example yet? Three top definitions and we don’t have a single tool for pursuing wellness. We depend on the brand creator.

So let’s get materialistic and check the science. This is from a paper in the Canadian Veterinary Journal.

One more point for enhancing already healthy people, and one less for wellness actually providing health.

It’s normal for a brand to have many definitions and uses. A brand’s definition changes over time and can embrace the opposite of its original meaning if that’s the way the market goes.

In a market without objective definitions, everything is wellness. Need proof?

Coca-Cola was a wellness product once. In the days when fizzy drinks were tonics packed with vitamins and electrolytes, sold at pharmacies, Coke was the invention of pharmacist John Pemberton. This was a sugar drink that helped people grow and stay active. For extra sharpness, he added a cutting-edge little nootropic called cocaine.

Pemberton called Coke a “brain tonic and intellectual beverage”, a “patent medicine”. This language came often with drinks containing cocaine and opium, considered exotic at the time. We see the same marketing in holistic energy drinks infused with matcha, yerba mate, and other exotic bull juice.

So, now that it’s phased out the cocaine and embraced decadence, how does the Coca-Cola Company treat its creator’s vision?

Huh. That explanation has more airy holes than a carbonated morphine substitute, which is what Pemberton originally planned for Coke to be after a Civil War injury led to his own morphine addiction (he was a high-ranking Confederate).

This shows us that you can change with the times. It also demonstrates that wellness has always dealt in fringe products, things that may or may not work. Everything might be a miracle. If it’s not, it will either disappear or pivot to sell what it really offers. It will step out from the wellness umbrella, which will go on undamaged.

But the brand is becoming a burden.

When I Google the word ‘wellness’ from my location of Melbourne, Australia, the results are almost all businesses. The exception is one Healthline article. One is a piece of brand content that says “... wellness trends we tried so you don’t have to.”

Amazingly, there’s no Wikipedia article in there. Google worships Wikipedia. A good Wiki page ticks every box of SEO and Google’s Needs Met model of importance, the latter sorted not by computers but by people trained to rank websites by hand. This is because on Wikipedia, ‘Wellness’ is a disambiguation page. The word is too vague, it has too many definitions. If I add the words ‘alternative medicine’ to my search, Wikipedia is back at the top. Well, it’s the second result after a list of local businesses.

In short, the word wellness is thousand-carat platinum for advertising. But it doesn’t have much other use.

Wellness doesn’t need to mean anything, and it might be useful to keep the definition flexible. If we’re perfectly, ultimately unable to agree on what it is, then we can ultimately (in a Heideggerian sense) agree on anything. And if we can argue about what something means forever, we can control the elevator pitch. If someone asks you “What does this product do?” you can answer with whatever you want the person to believe. Like truth itself, there’s Wikipedia’s wellness, the therapist’s idea of wellness, then there’s you, speaking your wellness into the market. As long as you’re speaking, as long as you hold the buyer’s attention, the whole brand is yours.

#SpeakYourWellness. You are well. You are optimised. You deserve it.